Feb 18, 2016

Eurex

Futures or ETFs? – Not as simple as yes or no.

There is currently a great deal of debate comparing the cost efficiencies of using ETFs over exchange-traded futures. To bring some objectivity to the table Eurex Exchange, the leading provider of MSCI futures and options, talked to Colin Bennett, author of “Trading Volatility”, the top ranked book on Amazon for volatility. In this article Colin offers his expert view on this hotly discussed topic.

Eurex: Historically asset managers have used futures for short-term positioning and hedging, however recently ETFs have been put forward as an alternative delta one product. What product do you believe is best, futures or ETFs?

Colin: There are many delta one products available, not only futures and ETFs but also total return swaps, CFDs and certificates/ETNs. A basket of cash equities can also be considered to be a delta one product, as a basket of EURO STOXX® 50 constituents gives the same 100 percent exposure to the index as other delta one products. While it is possible to compare funded delta one products such as ETFs, baskets of cash equities, certificates/ETNs against each other, it is difficult to compare these funded products to unfunded delta one products such as futures, CFDs or total return swaps. Any comparison needs to make assumptions on client funding, which varies by client, and also the embedded funding rate of the leveraged delta one product. For example, while LIBOR is often used as the risk free rate when calculating the fair value of a future, there have been times in the credit crunch when the implied funding rate of futures traded in line with overnight index swaps rather than LIBOR.

Eurex: So what you are saying is that in general you cannot make a sweeping statement that ETFs are better than futures or vice versa. Is there a "rule of thumb" that can be usually applied, i.e. short-term exposure is best via futures and long-term exposure is best via ETFs?

Colin: Exactly, you cannot say that futures are better than ETFs all the time or the opposite. If there was a delta one product that was always superior to another delta one product, then the inferior product would cease to exist as everyone would migrate to the superior one. The different delta one products are simply different wrappers to 100 percent equity exposure, and the choice of which is the best product depends on the client, the exposure the client is trying to achieve and the risk the client feels is acceptable.

As a “rule of thumb” futures are likely to be superior for short-term exposure, say a few months. For long-term exposure, say multiple years, ETFs are likely to be the best product as long as the total of the ETF expense ratio plus client funding cost (as the cost of a fully funded ETF position is the sum of expense ratio and client funding cost) is less than the annual roll cost (i.e. cost of each individual roll including trading costs multiplied by the number of times the futures position is rolled). This approximation is accurate if the borrow cost is relatively low and if the interest received on the futures margin is close to the risk free rate.

For example, if an ETF has an expense ratio of 16 basis points (and if we assume client funding cost is zero), then ETFs will outperform futures for long-term exposure if the roll cost (including trading costs) is more than 16 basis points (bp) per annum (i.e. more than 4bp per quarter). Pre-crisis annual roll costs (ca. 10bp including trading costs) were typically below ETF expense ratios, however since the crisis annual roll costs have been four times as large while ETF expense ratios have declined. This means that ETFs are now a viable (and usually cheaper) alternative to futures for long-term exposure.

Eurex: So if futures are best for short-term exposure, and ETFs usually best for long-term exposure, is it possible to calculate the “break even” point where an investor should be indifferent between futures or ETFs?

Colin: The exact “break even” where an institution is indifferent between futures or ETF exposure will depend on various assumptions, the most important of which are the ETF expense ratio plus client funding, and the assumptions of futures roll cost. To find where this “break even” point is, we need to sum all the costs and income from the two positions.

The cost of a futures transaction is the cost of crossing the futures market spread (bid offer of futures=BOf, which is smaller than the bid offer of the cash market for major indexes), plus the roll cost=R multiplied by the number of times you have to roll the position. If you own the position for “T” years and roll over “n” months, then “12T/n” is the number of futures contracts you own and one less than this value is the number of times you have to suffer the roll cost “R”. There is also the carry or running cost of the position which is equal to the funding cost of the margin (percentage of position to be margined=m, and normally you receive a lower rate of interest on the margin rm than implied interest rate of futures price rf), less the borrow cost received=b (as you receive all the borrow cost in the futures market).

Futures cost = BOf + (12T/n - 1) R + m (rf - rm) T - bT

We define the bid offer and roll cost to include all trading and exchange fees, and these two terms are the only terms that do not have to be multiplied by the length of time the position is kept=T (all other costs are a yield, hence have to be multiplied by time to get the cost). We note that rf -rm should be equal to the LIBOR-OIS spread if rf is the LIBOR and rm is an OIS (e.g. EONIA).

The cost of an ETF transaction is the cost of crossing the spread (due to creation/redemption process this is the same as bid offer in cash market=BOc), less the proportion of the borrow cost “b” received (proportion of borrow returned to investor=e, where “e” is usually 60-70 percent or less) plus the ETF fees or expense ratio (E) plus the funding cost of the fully funded position (F). To simplify the calculation the funding spread of the client “F” is defined versus the implied interest rate in the futures market (rf, which is normally close to LIBOR).

ETF cost = BOc - ebT + (E + F) T

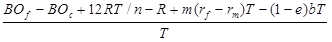

Therefore investors are indifferent between using futures or ETFs when the ETF expense ratio plus client funding (E+F) is equal to the below:

E+F(=ETF fees plus client funding) =

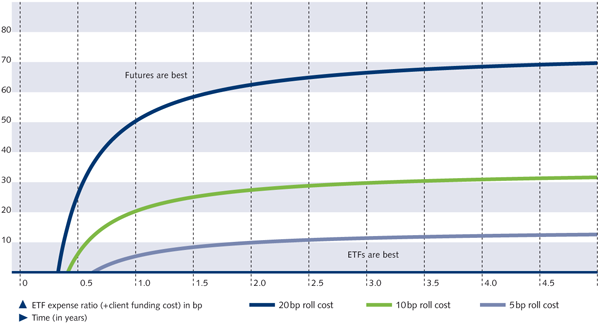

This equation using current data and assuming the quarterly roll cost (including trading costs) is 5bp, 10bp and 20bp per roll is given in the chart below. For short-dated positions (T small) futures are best (less rolls mean lower cost) and for high ETF cost (we assume client funding at 0bp) futures are best. Only for long-term positions (T large) and low cost ETF (expense ratio small) do ETFs outperform futures. Given the pressure on ETF fees this means ETFs are likely to outperform futures for positions of one year or more, and futures should only be used for short-term or tactical positioning.

The chart above shows you that if we have a time horizon of 2 years and a 5bp roll cost (including trading costs) every quarter, then you would prefer an ETF if it had an expense ratio of less than or equal to 10bp.

The assumptions we have made (to make the mathematics relatively simple) is that the bid offer spread (including trading costs) for the cash market (hence ETF creation) is 6bp, the futures bid offer spread is 2bp, the difference between the interest rate embedded in the futures price and what you receive on your margin is 5bp, you need 10 percent margin for the futures position, and borrow cost is 15bp (borrow cost is the third most important assumption after the futures roll cost and ETF expense ratio) with the ETF delivering 60 percent of the borrow cost to the investor.

Given the above assumptions the futures cost is = 2bp (bid offer) + 7×5bp (7 rolls at 5bp cost) + 10 percent ×5bp×2 (10 percent margin earning 5bp less than risk free rate for 2 years)-15bp×2 (receive 15bp borrow over 2 years). The total cost over 2 years for futures is therefore = 2+35+1-30=8bp.

Given the above assumptions an ETF with 10bp expense ratio costs = 6bp (bid offer) -0.6×15bp×2 (receive 60 percent of 15bp borrow over 2 years) + 10bp×2 (10bp expense ratio over 2 years). The total cost over 2 years for ETF is therefore = 6-18+20=8bp.

As both the future and the ETF (assuming 10bp expense ratio) have a total cost over 2 years of 8bp, an investor should in this case be indifferent between the two from a cost perspective.

Eurex: In order to carry out a back test, what factors do you believe are going to be key in determining which delta one product performs best?

Colin: When carrying out a back test you need to choose a time period you think is most similar to how things will be in the future. Given the structural changes that have occurred post credit crunch there is no historic period that closely resembles how the market is likely to be in the future. Trading costs have decreased over time, as have ETF fees, while at the same time the participation of proprietary trading desks has decreased. The reduction in arbitrage activity from proprietary trading desks make it less likely that futures will trade close to fair value in the short term, while in the medium term the imbalances caused by negative repo are likely to attract other participants. Given the permanent changes to the market caused by increased regulation, I would be sceptical of any back test that did not take into account the fact costs going forward are likely to be significantly different from historic costs. While this is difficult to estimate, a back test should adjust for how ETFs and future trading costs are likely to change over the coming years. While futures roll costs are currently inflated and likely to decline, ETF expense ratios could also decline due to increasing competition.

Eurex: What costs, hidden or otherwise, should be taken into consideration when comparing futures versus ETFs?

Colin: In addition to the implied taxation and borrow costs effects, an estimate of the futures roll cost needs to be taken into account. This roll cost tends to be cheaper for long rollers when sentiment is bearish, and more expensive when sentiment is bullish. For indexes whose constituents change, part of this roll cost could be offset with the cost an ETF suffers from rebalancing its constituents. While the cost of purchasing/selling the underlying shares in order to create/redeem an ETF lies with the client, all subsequent trading and rebalancing costs are absorbed within the ETF. As the futures market has a separate pool of liquidity to the cash market, the bid offer of futures is usually far smaller than for other delta one products. This difference will be particularly key for investors who have a volatile amount of inflows and outflows. In addition the implied tax rate of the futures market is typically less than the tax rate for non-domestic investors, as the presence of investors with a more advantageous tax rate can result in more competitive pricing of futures. While the pricing of futures typically includes announced dividends, for some maturities there is a significant portion of the price that incorporates implied dividends. Given the overhang in European and Japanese markets from the sale of structured products, implied dividends tend to be cheaper on average than the actual dividend. This imbalance is a negative for future pricing. As the implied dividend discount to the actual dividend is likely to narrow over time, the pricing of futures could improve going forward.

Eurex: What would you say are the pros and cons about using futures?

Colin: The futures market is unique in that it is the only listed leveraged delta one product. All other leveraged delta one products such as CFDs or total return swaps are OTC. While long only asset managers might not believe they require leverage, using products such as futures which have embedded leverage can help offset the drag due to being less than 100 percent invested. As asset managers often keep a cash float to handle redemptions and fund new investment opportunities, this means they are usually less than 100% is invested. When a fund receives new funds, there is not usually enough time to decide on individual investments. Going long the market via futures allows the beta to be 100%, while keeping cash on hand for future attractive investments. This is a strong argument for institutions always keeping a portion of delta one exposure in the form of futures.

While allowing leverage is, in theory, an advantage, for fully funded investors cash management could be an overhead. For example, if futures need 10 percent margin then an investor needs to invest the remaining 90 percent in cash. This can be a significant overhead for little gain in times of near zero interest rates.

The futures market is also the only delta one market with a separate pool of liquidity to the cash market. This means that large transactions can be completed quicker and easier with futures than with other delta one products (who have to access the cash market for all the members of the relevant index).

The primary disadvantage of futures is the cost, noise and overhead of rolling futures. As a future has to be rolled every quarter, and potentially every month, there is a significant overhead in deciding when to roll in addition to the overhead and cost of executing the roll. We note that rolling futures can at times actually lift performance, particularly when market sentiment is bearish and the futures roll is being driven by shorts, which makes the roll cheaper for long rollers. Recently the cost of rolling has increased for long rollers due to regulatory changes. Restrictions on balance sheet usage made futures a more attractive asset class versus long cash stocks, which lifted the price of both futures and futures rolls due to negative repo. In addition to increasing the cost of rolling for long rollers, regulatory uncertainty has increased the volatility or noise of the roll. Should short selling bans be reintroduced, this can also cause volatility in the futures market.

While net total return (NTR) futures avoid the risk of unknown dividends, as investors typically use the front month futures many near dated dividends would have already been announced. Futures on net total return indexes are (excluding the DAX®) typically are not that liquid. While using futures other than the front month future contract is possible, and would reduce the roll cost, in practice investors typically use the front month and roll as liquidity tends to be concentrated in the earlier maturities. However, that said, bilateral, centrally cleared, NTR instruments such as Eurex Exchanges’ MSCI futures - that are also supported by increasingly liquid order books - can offer a longer dated, leveraged alternative to longer dated ETFs or swaps.

Eurex: And from the other perspective, what would you say are the most and least attractive features about using ETFs?

Colin: A major advantage of ETFs is that they are a vanilla share. This means that they can be used by asset managers who cannot use derivatives such as futures. There is also a wider variety of underlyings for ETFs than for futures.

While the futures market has its own separate pool of liquidity to the cash market, ETFs are usually reliant on the cash market for liquidity through their creation and redemptions process. While the futures market can be multiple times the size of the cash market in terms of traded volume, ETF traded volumes are low and hence would be considered an illiquid product if it was not able to use the cash market liquidity via creation/redemption. For this reason the bid offer spreads of ETFs are often several times larger than that for futures. If an investor wants to “buy and hold” then these costs are not as significant as they would be for a shorter term horizon. However as an asset manager is expected to outperform the relevant benchmark, it could be difficult to explain to a client why there is a significant allocation to ETFs in a portfolio.

The fact that ETFs use the liquidity of the cash market does mean that there can be ETFs for an index that either does not have a futures market. If the futures market liquidity is dependent on the cash market (i.e. via buying the underlying stocks then buying an EFP, i.e. the underlying stocks are exchanged for a future in a similar way to the creation/redemption method of an ETF), then ETFs are likely to outperform futures as they have identical bid offer spreads (for major indexes the futures bid offer spread is smaller than the cash market) and futures suffer from roll cost. For example, major indexes will typically have a separate futures market pool of liquidity on futures however futures on the smaller sectors currently do not have a separate pool of liquidity.

We note that as ETFs typically pay dividends quarterly, they need to be reinvested potentially lifting trading costs. In addition, while the borrow cost is included in the bid and offer of a futures price, typically the borrow cost that is returned to investors through an ETF can be only 60-70 percent of the borrow received by the ETF provider. As the ETF is based in one jurisdiction the taxation of dividends will be based on the taxation in that location. We note that for the futures market, the implied dividend taxation rate can be in line with mid tax rates. This can be considered a natural side effect of the fact a long investor received net dividend, for example 85 percent of dividend assuming the tax rate is 15 percent, while a short investor pays gross or 100 percent of dividends. As for every long in the futures market there is a short, the market often trades in line with mid tax rates, or 92.5 percent for a market with 15 percent withholding tax. Using futures can mean a higher implied dividend is received than the net dividend from a physical ETF. If an ETF is swap-based then the implied dividend tax rate in the swap should be similar to that for the futures market.

Eurex: So if an asset manager asked you if they should use futures or ETFs, what would you say?

Colin: I would recommend an asset manager always keep a small futures position to enable them to be 100 percent invested (as the leveraged portion of the futures position means an asset manager has cash on hand to handle redemptions). For the remaining position I would recommend futures for a position that is likely to be kept for less than one year, and ETFs for a position likely to be kept for one year or more. Should the cost of a futures position and ETF position be nearly identical, I would always recommend ETFs as they avoid the overhead and noise of futures rolls and cash management. I would note that asset managers who allocate a significant portion of their assets under management to ETFs run the risk of being an expensive index tracker.

About Colin Bennett

Colin Bennett is the author of 'Trading Volatility', the top ranked book on Amazon for volatility. Previously he was a Managing Director and Head of Quantitative and Derivative Strategy at Banco Santander, Head of Delta 1 Research at Barclays Capital, and Head of Convertible and Derivative Research at Dresdner Kleinwort.